History/Society/Culture

March 15, 2016

Beef in Ancient India

Dilip Das (St. Louis, Missouri, USA)

(the original Bengali version will be found here)

The University lecture hall was full. The topic was so attention-grabbing, that students, professors, staff and even some parents filled up all the seats before the debate started.

The debate originated few days earlier at the University playground. It was a bright Friday afternoon, some students were relaxing and chatting around the playground while some played cricket. Everyone turned around when Udayan and Ruma started another round of their numerous debates. But this time, the subject was new - whether ancient Indians used to eat beef or not. Their debates have always been fascinating and worth listening, where scimitars of their knowledge and intellect flashed in the duels. Therefore the commotion of the debate attracted a lot of audience and the cricket game fell apart.

The debate was still in the initial stages when two well-known personalities pushed through the crowd to come forward. They were the Dean of Students Sumit and head of Sanskrit department Suromoyee. Both of them felt that such a debate is very relevant to the present circumstances in India and it should not be held in a playground, cafeteria, commuter train or someone’s blog. The right place for such a debate is the University lecture hall, where many scholarly persons would be able to attend and listen to the arguments. They made an impromptu decision that the debate would be held at the University lecture hall next Saturday afternoon.

The lecture hall was overflowing with enthusiastic people when the debate started next Saturday.

Other than Sumit and Suromoyee; Keya, a professor of Chemistry and eminent writer herself, and Bhaskar, a professor of Electrical Engineering and the editor of popular magazine ‘Uttaran’, were the judges in the debate. Subject of the debate was “Beef eating was prevalent in ancient India”. Ruma argued for it and Udayan against. The debate followed a question and answer format.

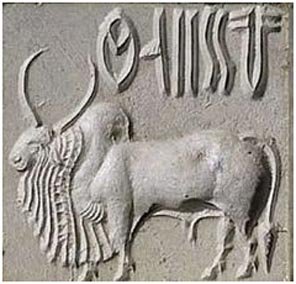

Suromoyee introduced the subject describing the importance of cows in ancient India. Cows were very valuable to the Rig-Vedic Indians. Rich persons used to be called gómat and tribal leaders were called gópa or gópati. There used to be pitched battles among the ancient Rig-Vedic Indians, which were called góviṣṭi, gavyu and gaveṣaṇa. Even the word duhitā or daughter means the one who draws milk. Puraṇic mythologies are full of sacredness of cows and her divine tales. Stories extolling the virtues of cows or oxen are also found in other ancient Indo-European cultures like Norśe, Irish and Iranian cultures. Also, we have seen the picture of the huge Ox on the Harappan seal. Hence, in view of the ancient glories of cows, we are expecting a lively debate today.

Huge Ox on the Harappan seal |

Right at the outset the Dean of students Sumit clarified that the subject of the debate was complex, sensitive and very relevant for the present times. This has been debated in the past and shall continue to be debated in future. The purpose of the debate was educational and not to hurt anyone’s religious or other feelings.

Udayan’s stared with a tough question, aiming to hurt his opponent right at the kickoff. He said, ‘A clear proof of inviolability of cows is in the Ṛg Veda, in maṇdala one, sukta 164, verse 40 ’ addhi tṛṇam aghnye viśvadānīm piba śuddham udakam ācarantī ..’, where the cow has been called aghnya and in verse 27 ‘duhām aṣvibhyām payo aghneyeyam sā vardhatām mahate soubhagāya’ where the cow has been called aghnyā. Additionally, cow has been glorified as inviolable in tenth kanḍa of the Atharva Veda. Do these not give ample evidence that cow was inviolable in ancient India?’

Everyone in the audience thought the debate got settled before it even started. But Ruma had other ideas. She replied, ‘Not only aghnya or aghnyā, cow has been calledin many other glorifying names in the Ṛg Veda. Aghnya or aghnyā have been mentionedfour times in the Ṛg Veda and 42 times in the Atharva Veda. Cow has 21 synonyms like gau, usra, usriyā, dhenu sudugdhā, vṛṣa etc., and has been mentioned about 700 times in the Ṛg Veda. The introduction given by Suromoyee mentions some of the reasons for such glorification of cows. In the Ṛg Veda, cows were not viewed simply as animals; they held a special position in Vedic society, economics and religion. Let me give some examples about the position of cows in the Ṛg Veda. Agni has been called ‘…vṛṣabhaś ca dhenuh’, he is both the cow and the bull. Soma has been called ‘…priyaḥ patir gavām’, he is the Lord of Cows. Surya has been called a bright colored bull, Indra has been compared with a dhenu, Vṛhaṣpati has been called gopati, and Marut has been addressed as govandhu. Cows’ milk has been compared with bright cosmic rays. Cows have been called mother of Rūdra, daughter of Vasus, sister of Aditya and affectionately given the names Aditi, Ṛta, Vāk, etc. Some gods were thought to be originated from cows and called gojāta.

Such glorifications of cows were nothing but figurative use by the Ṛṣi-poets of ancient India, both allegorically and metaphorically. Such figurative use is found not only in India, but in mythologies of every ancient civilization. Thus, in spite of metaphorical use of aghnya, because cows were used as the sacrificial beasts in different yajñas where people ate beef. Hence, cows were not truly inviolable’.

Udayan landed a vigorous counter-attack as soon as Ruma stopped and said, ‘I do not agree with your explanation. Think it yourself, if cows were so beloved and important, then why should they be sacrificed or their meat eaten?’

Ruma laughed at Udayan’s animated aggression. She said, ‘Like present days, even in ancient time we used to offer our best and dearest things to the gods. That is why we see cows and bulls as sacrificial animals, among others. For example the 169 sukta of 10th maṇdala in theṚg Veda, dedicated to the Cow-god, states that the cows give up their bodies in sacrificial fires for other gods. In the 86th sukta of the same maṇdala, Indra, one of the most important gods of the Ṛg Veda, is seen bragging to his wife that he could eat fifteen or twenty oxen. In the 41st sukta of 8th maṇdala, Agni is offered various meats including horse, ox, bull and vaśa. Though there are differences in opinion about the true identity of vaśa, many experts think it is barren or non-milch cow. In the Taittiriya Samhita of the Yajur Veda, the list of animals to be sacrificed for Aśvamedha yajña contains cows. The gosava portion of the Rajasuya and Vajapeya yajñas described in the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa of the Yajur Veda, has similar descriptions. Many other different yajñas like Agniṣṭoma, Darśapurṇamasa, Caturmasya, and Soutramaṇi have cow sacrifice in the paśubandha portion of the sacrificial ritual. This conclusively proves that the adjective aghnya was used metaphorically in the Vedas’.

Udayan never gives up easily. He said, ‘Your arguments are not fool-proof. Sacrificing an animal does not mean consuming its meat.’

Ruma jokingly said, ‘As far as I can remember, in your ancestral home you follow the ritual of sacrificing a black goat on the third day of Durga Puja. And I also remember to have seen you gluttonously devouring that goat meat. Right?

Everyone burst into laughter at Ruma’s humor. Even the judges smiled. Ruma continued, ‘Actually many of our present customs and rituals have their roots in our ancient days. The seventh chapter of Aitareya Brāhmaṇa gives an accurate description of how the sacrificed beast would be distributed among the priests. Taittirīya Samhita also has similar description of piecing off the animal. The Gopatha Brāhmaṇa of Atharva Veda describes how the Samitār, the sacrificer, should divide the animal in 36 parts. In the third and fifth chapters Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa declared ‘paṣvo vai annaṃ’ and ‘annaṃ vai paṣvo’. In the third chapter the Taittirīya Brāhmaṇa clearly stated ‘atho annaṃ vai gauḥ’, meaningcow verily is the food. Please rememberthe famous statement by Ṛṣi Yājñavalkya, in the third chapter of the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa,where he said that he liked beef, only if it was ‘aṃsala’, which is interpreted as ‘tender’ by many experts. These leave us no doubt that beef was a food for ancient Indians’.

Udayan sharpened his attack, ‘Cow has been clearly and conclusive described as inviolable in fourth and fifth kanḍa of the Atharva Veda and it is reminded that that anyone killing a cow would be ‘mṛtyu paśeṣu vadhyatām’, meaning ‘would be ensnared by death’. Kings have been reminded that a brāhmaṇa's cow is anadyam, meaning inedible. Would you still argue that cow used to be eaten in those days?’

Ruma paused a little while to catch a breather and then opened her mouth again. ‘I would request you to consider every quote with reference to the context in the source. These verses were written to remind everyone about their holy duty to give dākṣiṇā or sacrificial-fee of cows to brāhmaṇas and the consequences of any deviation from such a duty. In other words, these verses say, ‘folks, brāhmaṇa's cows are sacred, stay away from them; don’t ever think of eating them’. Here the brāhmaṇa is the source of sacredness, not the cows. Remember that it is generally believed that the Atharva Veda has been redacted much later compared to the other three Vedas. Actually, the caste-less society of Ṛg Veda has been undergoing an evolution. Brahmanism was on the rise with brāhmaṇas claiming their supremacy over the other three ‘varṇa’, loosely translated as castes, in the society. These sūktas are examples of such preeminence by the brāhmaṇas. These sūktas also imply that in those days, a certain outlook against cow-slaughter was gradually emerging, primarily among the brāhmaṇas.’

Udayan was indomitable. He counter argued, ‘Vedic language is archaic and different people interprets them differently. Thus, your interpretation may not be acceptable to all. If we take a look at the post-vedic literature, we see that in the first chapter, fifth paṭala of Āpastamba Dharmasūtra, beef is prohibited along with meats of one-hoofed animals’.

Ruma interjected and said ‘Let me address your first doubt. Yes, we know that Vedic Sanskrit is pre-Pāṇini and archaic. But the interpretations I used are followed by many eminent Sanskritists and Indologists. Now, let me take up your second argument quoting from Āpastamba Dharmasūtra. Like you, many others quote from the ancient texts disregarding the context. The section of Āpastamba Dharmasūtra you mentioneddescribes edible and inedible foods and the exact part quoted by you prohibits eating of one-hoofed animals, camels, boars, śarabha and gayal, conspicuously not cow. Interestingly the very next verse tells us that cows and bulls are edible. I would also like to add that in the same chapter, the author prohibits eating of onions, garlic and chicken. Thus, if you really wish to follow Āpastamba Dharmasūtra entirely, you would need to stopeating chicken too.

Now let me cite some examples of beef eating from the Gṛhyasūtras, which are also post-vedic and contemporary to the Dharmasūtras. In ancient times, eating cow or other animal meat was not restricted only to sacrificial rituals. People used to eat beef at social ceremonies too. For example, at the end of the social festival gavāmayaṇ, three barren cows were sacrificed to Mitra-Varuna and other gods. You may know that a mix called madhuparka used to be offered to respected guests like teacher, graduate, priests, father-in-law, king, etc. At present we put curd and honey into madhuparka, but in ancient times, people would put beef in it. I do not know how it tested, but the practice of offering beef in madhuparka has been mentioned in various Gṛhyasūtras like Āpastamba, Govil, Hiraṅyakeśi and Saṅkhayaṇa. Even one sutra in Pāṇini’s Sanskrit grammar Aṣṭādhāyi has a reference to offering beef for guests. Pāṇini wrote ‘daśgoghnau sampradāne’, as an example of use of dative case. Here daṣa is the one to whom offering or donation is made and goghna indicates for whom a cow is killed. If you are interested to know more about it, you may like to consult the book ‘History of Dharmaśastras’ by Bhārata Ratna Pandurang Kaṇe.

Some ancient Sanskrit literatures, written after the Dharmaśastras, also contain references to beef eating. For example in the fourth act of Bhavabhūti’s Uttararāmacarita, there aee some funny dialogs about beef eating. When Ṛṣi Vaśistha arrived at Valmiki’s hermitage, one disciples of Valmiki asked another, ‘ who is this bearded guy, Is he a tiger? He ate the poor tawny cow to satisfy his appetite. Bhavabhūti did not write anything about digesting a whole calf! In Varāhamihira’s Bharatasaṃhita, there is a mention of cow as eatable among other animals. I could cite multiple examples from the epics, the Rāmāyaṇa and the Mahābhārata, but since they are just epics, not history, I am giving only one example. In Vaṇaparva of the Mahābhārata, there is a story that two thousand cows used be killed daily for the kitchen of KingRantideva. The same story is again mentioned in 46th verse of Meghadūtam by Mahākavi Kalidāsa, where the Yaksha is requesting the cloud messenger to visit and pay respect to King Rantideva, who created a river of bovine blood. I hope now you will agree with my arguments’.

After speeding through this far, Ruma slowed down and almost stammered, ‘Well, Um, I have one more thing to add. Though the Bṛihadāraṇyaka Upaniṣada is not a part of the Dharmaśastras or Sanskrit literature, beef eating has been mentioned in the sixth chapter, which is believed to be more modern than the rest. I think you know which one I am referring to.

Udayan looked at Ruma through the corner of his eyes and nodded in affirmative.

Judge Keya interjected, ‘How come you two know some parts of the Bṛihadāraṇyaka Upaniṣada, evenmutually agree, but do not tell us which one is it?’

Judge Suromoyee smiled, ‘Well, she is being shy to tell us all that in detail. It is written that if any couple desires a child with long life and well versed in all the Vedas, they should cook and eat bull meat with clarified butter’.

The whole house burst in laughter. Ruma blushed.

Udayan continued where Ruma finished and said, ‘We find continuous growth and influence of inviolability of cows in the Smṛiti sutras like the Manu Smṛiti. It is well known that the Manu Smṛiti was the first Hindu code of law. In the fifth chapter of his book Manu has written a lot against non-vegetarianism in general. He said that abstinence from meat for the whole life is equivalent to one hundred Aśvamedha yajña. He goes on to tell us thatone who ate animal meat in the present life will be eaten by that animal for as many years as the number of hairs on its body. In eleventh chapter cow slaughter has been called a crime. Cows figure nowhere in the list of edible meats prescribed by Manu. Does this not prove embargo on beef in ancient India?’

Ruma smiled at Udayan’s argument and said, ‘Before I answer your question, I need to explain the era and historical perspective of Manu Smṛiti. It was believed to be written around 200 BC to 300 AD, when Buddhism was firmly established in India. Thus, it is normal to expect some influence of Buddhist philosophy of ahiṃsa in the fifth chapter of Manu’s book, where he advocates vegetarianism. Somewhere else in the same chapter Manu has written it is ok to eat sacrificial animals, because they were created for such purposes. Eating sacrificial meat is ‘daivo vidihiḥ’, the divine rule. Yet in one other place he wrote that there is nothing wrong with ‘meat, wine and carnal pleasures’, because they are human nature. In tenth chapter he described how one Ṛṣi had to eat beef in a deep forest to avoid starvation. Hence, your argument based on Manu does not hold ground. Criticism of Manu Smṛiti is not the topic of today’s debate, but I would like to point out that such contradictory passages are found in plenty in this book. This is because it was written by not one, but multiple authors’.

Udayan immediately fired back his choicest weapon, ‘Now listen what Ṛṣi Parāśara has written about ancient laws. He has spent almost the entire ninth chapter of his Parāśara Smṛiti clearly forbidding any harm to cows and debarring beef eating. He also prescribed the Kālasūtra hell for people who kill a cow. In eleventh chapter he said a brāhmaṇa is not allowed to eat beef and needs expiation if he does it. Similarly in Vyas Smṛiti, the author said that a beef eating brāhmaṇa should be relegated in society. Do you still have any doubts about prohibition of beef in ancient India?’

The entire hall fell silent. Ruma was answering promptly so far, but she was silent momentarily. Smile disappeared from Ruma’s friends’ faces. Audience thought Ruma finally conceded.

Ruma took a deep breath, had a quick glance at her supporters and spoke, ‘Let me first tell you something about Ṛṣi Parāśara. He was not the same person as the father of Veda Vyāsa, author of Mahābhārata. He was a different person and belonged to a much later time. This is confirmed in the first chapter of his book where he said Manu Smṛiti was for the Kṛta or Satya Age and the Parāśara Smṛiti is for the Kali Age. It is generally believed that he belonged to the middle ages. Right towards the beginning, Parāśara describes the duties of all four varṇas and reminds us about the brāhmaṇas’ supremacy in the social hierarchy. Per Parāśara Smṛiti, even a brāhmaṇa of questionable character is better than a continent chaṇdala. If a brāhmaṇa kills a chaṇdala, then he gets off with a very light expiation of bathing and chanting the Gayatri mantra. This clearly explains how deep rooted the varṇa system became during his time, wherein lies the main reason for Parāśara’s prohibition of beef.

You mentioned that in the ninth chapter Parāśara described the sins of hurting or harming a cow. Please go back a little and you will find in the eighth chapter he stated that sins of killing a cow can be expiated by feeding a few brāhmaṇas, ‘brāmaṇānbhojayitvā tu goghna śuddhey na saṃśayaḥ’. The kṛccha-cāndrāyan expiation has also been prescribed for eating beef. It is clear that though it might not be widely prevalent, beef eating did exist and it was not considered a major sin. Parāśara’s prescription of staying away from beef can be viewed as an attempt to save the brāhmaṇas’ cows, which were a major source of their income. If prohibition of beef was really serious, then why do we find beef as a medicine in the Ayurvedas? In the 27th chapter of the CarakaSaṃhita of Ayurveda, cow has not been placed among gods, but among 29 types of ‘prasaha’ animals like tiger lion, horse, etc. who bites off their food. In the same chapter beef has been prescribed as a medicine for various diseases.

But if you wish follow Parāśara Smṛiti to the word, then along with giving up beef you need to follow everything in it, not only the ones you feel convenient. Here are some of things you need to do if you follow Parāśara. You cannot eat standing or facing south. Younger brothers cannot marry before the elder brother for fear of entire family going to hell. A dog bite can be cured simply by bathing in water touched with gold and eating clarified butter afterwards, without any need for shots. And if your pet dog smells or licks you, then you become truly impure. Now you tell me if you wish to follow Parāśara Smṛiti or agree with me’.

The entire hall ruptured with claps.

Ruma continued, ‘To tell the truth, it is very difficult to follow Manu or Parāśara in this 21st century. First, the Smṛitis were mainly prescriptive, they were some directives given by the brāhmaṇas. The Smṛitis were by no means fully descriptive of the prevailing customs in that time. The proclaimed ‘laws’ were mainly intended for kings and rich and famous of the society, to keep them under brāhmaṇic influence. They were not for the rank and file. Secondly, Manu Smṛiti and the other Smṛitis are not monolithic, homogenous and written by one person. Many authors contributed into them from time to time, spanning hundreds of years. Thus, they are often self-contradictory and impractical for the current times’.

Udayan cannot be subdued so easily. He continued, ‘Now I would like to give some examples against beef eating from Kauṭilya’s Arthaśāstra. The thirty-sixth chapter of this book describes the morning duties of a king, which includes circumambulating a cow with calf and a bull. In the twenty-ninth chapter superintendent of the royal butchery has been instructed not to kill any calf, bull and milch-cow. The superintendent of royal herds is reminded that harming or stealing a cow entails death penalty. Do these not prove inviolability of cow and prohibition of beef?’

Ruma immediately retorted, ‘No, they don’t. First, I would like to remind you that today’s debate is not about respecting or worshipping cows. It is about eating beef in ancient India. Second, please investigate further and you will see that the death penalty you mentioned was only for the royal herd, not for the subjects. Third, please note that in Kauṭilya’s instruction of not to kill cows included only calves, bulls and milch-cows, other cows were excluded from the prohibition. The best proof of my argument lies in the twenty-ninth chapter where the author says if a cow dies of natural causes, it is okay to sell the meat, dried or fresh, but the hide is a royal property. This proves there was no prohibition against beef’.

At this point the judges started asking questions. Judge Keya asked, ‘Ruma, so far everything we heard from you have been from the Sanskrit literature. Don’t you have anything outside that to support your arguments?

Ruma replied instantly, ‘Sure I do. First let me cite some examples from the Buddhist Pali literature. We all know that Buddha was against animal slaughter. Sutta Piṭaka is a part of the Pali Canon Tripiṭaka. Majjima Nikaya, a part of the Sutta Piṭaka, has two phrases, ‘dakkho goghātaka’ which means an expert cow-butcher and ‘goghātaka antevāsī’ meaningan apprentice cow-butcher. It does not need a second guess about what these professions did. In the Sanyukta Nikaya, another holy book for the Buddhists, there is a story about how Buddha prevented Prasenjit, the king of Koshala, from sacrificing almost a thousand cows and other animals in his yajña.

Now I would like to present a few examples of ancient Tamil Literature. In ‘Akananuru’, a part of two thousand year old Sangam literature, the verses 249 and 265 have the descriptions of gangs of bandits eating roasted fat calves’.

Judge Bhaskar asked, ‘I am a scientist. Your arguments are all based on literary examples, written by some ancient Ṛṣis long ago. Can you support your arguments with science?’

The answer came from Ruma. She said ‘Modern archeology is a science. Thus, my examples will be from archeology. First, let me discuss the edicts of Emperor Aśoka, who firmly based his ‘dhamma’ on ahiṃsa. In his fifth pillar edict Aśoka asked his subjects not to eat certain animals. This list contains many known and unknown animals and curiously even ants, but cow is conspicuously absent there. I am inclined to say that Aśoka knew that beef formed a staple diet and a prohibition was impractical.

But the most important proof of beef eating is found underground. Archeologists have excavated all around India and found animal bones thousands of years old. Cattle bones have been most numerous among those. Archeologists found something interesting in those bones, many of the cattle bones have been chopped and burnt. They believe these bones are sure proof of cattle being eaten in those periods. Such chopped and burnt bones have been found not only in one place, but at many sites all over India, right from the Harappan age to the historic ages. One such site is the ancient town of Hastinapura, believed to be in present Meerut district of Uttar Pradesh. Thus, even science gives us the proof of eating beef in ancient times’.

Dean of students Sumit shot the next question from the judges’ seat, ‘I understand that in the Vedic age cow was adored and compared with gods, but there was definitely no prohibition on eating beef. But after 1500 to 2000 years, in various Puranic mythologies and Smṛiti literatures, we find that divinity was imposed on cows and beef eating has been considered a sin. Tell me more how did this evolution take place? What were the drivers behind it?’

Everyone was surprised at Ruma’s answer. She said, ‘Sir, Udayan knows the answer to your question better than me. I would request him to explain this’.

A surprised Sumit asked, ‘Isn’t he your opposition, arguing against you in this debate? Why should he reply on your behalf?

Ruma smiled, ‘He is my opposition simply for this debate. In fact, for months we have been researching on this topic together. I know all his arguments and he knows all of mine. Your question came to us also, but Udayan completed the studies about the evolution before me. Thus, he is in a better position to answer your question’.

Audience clapped whole heartedly at Ruma’s reply.

Udayan started in his usual baritone voice. ‘Your question also came to the mind of a great scholarly person named Al-Beruni, about one thousand years ago. He came to India from Persia, learnt Sanskrit and wrote a book ‘Tariq-Al-Hind’ on the history of India. In the sixty eighth chapter of the book, he gave a list of items considered edible and inedible for Indians. Beef is found on the inedible side of the list. Al-Beruni asked many Indians about the reasons for not eating beef and received some interesting replies. Some said that in ancient times, even before King Bharata, Indians used to eat beef and sacrificed cows in the yajña. But no one knows why we stopped. Some said it is all because of betel leaves we chew. The betel leaves make our bodies hot, which coupled with beef which is also hot, make our body dehydrate! Actually, Al-Beruni wrote whatever he saw or heard. He did not dig into the facts and explore the reasons. If he would have researched the socio-economic evolution of the Indian society since ancient times, he would have found his answer.

Suromoyee has told us the position of cows in the pastoralist society of Vedic era. Cows used to be the money, cows were central to the economy. We have an interesting story of a group of people called the Paṇi, who stole Indra’s cows. The enraged Indra sent Sarama the divine bitch, to warn the Paṇis to return the cows or face dire consequences. This story shows the importance of cows even for the all-powerful Vedic god like Indra.

Two important things happened in course of the evolution in the next 500 to 1000 years, especially in northern India. The first one was establishment of the varṇa system, which was originally intended to delineate professions into four varṇas, and the consequent rise of Brāhmaṇism. The second one was widespread use of iron tools in agriculture, war and clearing of forests. In the sixth century BC we find sixteen Mahajanapada orlarge inhabited urban clusters in northern India. Rise of the Mahajanapada led to diversification of different professions with gradual reduction in reliance on agriculture and pastoralism. In the tenth chapter of his Smṛiti, Manu gave an example of four professions by local inhabitants. The Ambastha were expert in medicine, Sūta were experts in charioteering, Vaidehaka were experts in service for women and the Magadha in trade. The Greek ambassador Megasthenes found people of various professions in Pāṭaliputra during Candragupta’s time. With diversification of professions, economy enlarged and importance of cow reduced. Economic needs witnessed the emergence of the punch-marked coins, the first version of money, around sixth century BC which became widespread during the Mauyran era. Thus, with rise of monetary economy, cow was no more the economic spine or main mode exchange. It was possible for people to live a decent life without owning cows.

Punch-marked coins |

But the importance of cows did not change in the life of the Brāhmaṇas. Thye followed the old system of dakṣiṇā cow, received as the statutory sacrificial fee or honorarium. Ruma mentioned about brāhmaṇas occupying the top layer of the society and rising influence of Brāhmaṇism. In the Smṛitis, brāhmaṇas are prohibited to plow the field for agriculture. Even now, this sentiment reverberates in rural India. Smṛitis are full of instances where a sin can be atoned by donating cows to brāhmaṇas. Hence, cows received either as dakṣiṇā or donated for expiatory purposes,became a chief source of income to the brāhmaṇas and the phrase ‘go-brāhmaṇa-hitāya’, meaning ‘for the welfare of cow and Brāhmaṇas’, was made popular. In the eleventh chapter Manu told us the sin of killing a Brāhmaṇa can be atoned by simply being ‘go-brāhmaṇa-hite-rataḥ’, that is by being virtuous to the cow and brāhmaṇa. Thus, the two elements ‘go’ and ‘brāhmaṇa’ got very much intertwined in the prevailing social customs. We also find these two words in an important archeological monument, the Junagaḍ rock edict of Śaka Kṣtrapa Rudradāmaṇa, dated around 150 AD. Thus, it can be assumed that the sanctity of cow started to get ground around the first century AD. But that became consolidated after divinity was attributed on the cows in the principal puraṇas during fourth to fifth-sixth century, around the Gupta era.

Here, I would like to tell a story from the Bṛihadāraṇyaka Upaniṣada, characterising the importance of cows in ancient India. In the third chapter of this book, we find at a certain yajña, king Janaka of Videha wanted to gift one thousand cows with their horns wrapped in gold, to one brāhmaṇa who is considered Brahmiṣtha, meaning one who has known the Brahma. Ṛṣi Yājñavalkya stood up and asked his disciples to take all the cows home. The other brāhmaṇas jointly questioned Yājñavalkya how did he consider himself as the Brahmiṣtha. Yājñavalkya said, ‘Salutations to the Brahmiṣtha, but right now I need these cows very much’. This story tells us how the cow was considered as very essential and important wealth for the brāhmaṇa.

But it becomes a problem if people start eating the venerable cows, purposed to be given to a brāhmaṇa as a dakṣiṇā. This reduces the brāhmaṇas’ potential cow-wealth. Therefore, they started writing the Smṛiti literature, prohibiting eating beef, among other things. Cow became ‘kalivarjya’, prohibited in the Kali age. Since the brāhmaṇas were at the top of the social hierarchy, people were warned that ignoring their infallible ‘law’ could be a sin. Smṛitis told everyone that eating beef was sinful and beef-eaters were destined to various hells in after-life. Thus sacredness was imposed on cows, while the main economic reason lay buried under the heaps of such prohibitory directives. But it is interesting to note that in the Smṛitis cow-cow slaughter has been considered as ‘upapātaka’, a minor sin, compared to brāhmicide or drinking alcohol, which are ‘mahāpātaka’, a major sin. That is why Smṛitis tell us that just by feeding some brāhmaṇas one could expiate the sin of cow slaughter. Brāhmaṇas also gained from the punishments meted to various offences committed by people. Many offences could simply be expiated by donating cows to brāhmaṇas. Sūtra literatures tell us that if a Kṣtriya or Vaiśya murdered someone, a number of cows were to be given as compensation to the next of kin of the murdered person. Initially, the cows were handed over to the king, who added a bull or two and passed on the entire herd to the murdered person’s family. Later somehow this practice changed and the cows were directly given to the brāhmaṇas. Thus, all kinds of strategies were adopted to enlarge brāhmaṇas’ cow-wealth.

One issue arose about the upkeep of the cows owned by the temple priests. The cows needed a large space for cow-pen. This was resolved by attaching cow-pens to temples. A fourteenth century copper plate mentions construction of a large cow-pen attached to the temple of Padmanāvaswāmy. Since the cows virtually belong to the god, eating their meat became inconceivable.

Cow worship |

Some experts give another reason for imposing sacredness on cows. Ruma told us in the beginning how cow has been figuratively described in Vedic literature. With passing of time, such figurative meanings became more and more obscure and people started taking them literally, culminating in attribution of sanctity on cows. Please remember that the Vedas were transmitted orally, that is why we call them Śruti.

Around the same time, several mythologies in various Puraṇa were crafted to firmly establish the divinity of cows. Stories like Surabhi, Kāmadhenu and ritualistic elements like Pañcagavya were the results of such efforts. But though cow has been compared to gods and worshipped through ages, I am not sure if there is any temple of ‘gomātā’ in India. From this aspect, the bull is more fortunate. It is worshipped along with Śiva and there are two large Bull-Temples in the state of Karnataka.

Bull-Temples in the state of Karnataka |

A question that follows naturally is that how rigidly the beef prohibition prescribed in the Smṛitis were enforced. Al-Beruni wrote Sūdras used to eat beef. Eminent historian Romila Thaper in her book Early India said the beef prohibition was restricted to upper castes only. Therefore, the beef prohibition prescribed in Smṛitis was not widespread in all strata of the society.

Apart from the socio-economic evolution, two other important factors brought significant changes to the Indian religious panorama. The first one was the doctrine of ‘Ahiṃsa’ preached by the Buddha. He was totally against the sacrificial rites and killing animals for that purpose. Buddhism spared many animals from being butchered. With spread of Buddhism many turned to vegetarianism and this could be another reason for reduction in beef eating around 3rd-4th century BC, which has been archeologically supported.

The second factor was worship of the formless Brahma predicated in the Upaniṣada, which precluded sacrificial rituals and animal sacrifices. Ruma mentioned an undercurrent of uneasiness against animal sacrifices during the Vedic Ages. A story in the second chapter of the first kanḍa in Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa alludes to this sentiment. The story says that in the beginning gods wanted to use the Man or Puruṣa as the sacrificial beast. When he was used in sacrifice, the sacrificial quality went out of him and entered a horse. This kept repeating from the horse to bull, ram, billy goat and finally the sacrificial quality entered the ground. The gods dug up the earth and got rice and barley. Thus, oblation of rice and barley is fivefold more potent than animals. In Aitareya Brāhmaṇa, Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa and Manu Smṛiti, we find reference to ‘piṣṭapaśu’, an effigy of an animal made with rice and barley that could be substituted for animals in sacrifice. This could have helped in reduction of animal sacrifice, though experts are unsure to what extent. Perhaps, in a distant time in history, bloods flowing from the sacrificial animals made a certain Ṛṣi cry in his heart and he asked the question, ‘Why there is so much blood? The Almighty is omnipresent in every living and non-living being. He is verily what I am. Then why should we shed so much blood killing poor creatures’. That is why the Ṛṣi-poets of Upaniṣada prayed for us to be led to the light of true knowledge from the darkness of ignorance, to immortality from the futility of death’.

Suromoyee glanced askingly at Udayan after he stopped. He nodded, he is done. Suromoyee said, ‘This concludes our debate for today’. Someone from the audience asked who won the debate.

Suromoyee replied, ‘There is no question of win-loss in this debate. This debate has not been organized for that purpose. This was for educational purpose, to disseminate the facts. This was also to enlighten people how the Indian society has been evolving since ancient times. My student Ruma has brought her labored research in front of everyone. We have seen that our ancient Śastras have argued this in both ways and sometimes the same Śastra has contradictory arguments. Udayan explained in detail the root causes of arguments against beef eating.

In a democratic society like ours, eating habits are personal preference of people. We do not foresee any need for Śastras’ interpretationin this area. For example, if people follow the old adage 'misṭannamitare janāh' andstart feeding sweets to a diabetes patient, then the results could be disastrous for that person. Hence, people should follow their own taste, health, and of course doctors’ advice while making choices about food. Like many other details in our daily lives, I do not see any scope of Śastras here’.

Professor Bhaskar Basuroy asked Udayan, ‘Hey you, you’re a student of our Electrical Engineering. How did you learn all that Sanskrit?’

The reply came from the audience, ‘Sir, by hanging out with Ruma’. The hall filled up with a combined laughter.

Acknowledgements:

Profrssors Doris Meth Srinivasan and Dipak Bhattacharya have seen the manuscript and offered valuable comments. Prof. Bhattacharya helped me interpreting the Paṇini sutra. They are both noted Sanskritist and Indologist. I am grateful to them for sparing time for me in spite of their preoccupation with research/teaching.

Prof. Dilip Chakraborti, well known among historians and archeologists, suggested B.P Sahu’s book on archeology, which helped me in eliciting the archeological facts. Dr. S Palaniappan helped me with translation of the Tamil verses. I am grateful to both of them.

Main Sources.

D.N. Jha - The Myth of the Holy Cow, Verso, London, 2002

Debiprasad Chattopadhyay - Science and Society in Ancient India, B R Grüner B V, Amsterdam, 1978

B.P. Sahu – From Hunters to Breeders – Faunal Background of Early India, Anamika Publication, Delhi, 1988

Doris Meth Srinivasan – Concept of Cow in the RigVeda, Motilal Banarasidas, Delhi, 1979

W Normal Brown – The Sanctity of the Cow in Hinduism, The Economic Weekly, Feb 1964, Madras

Other sources are mentioned within the article.

Dilip Das, a graduate of Jadavpur University, Kolkata and Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, currently lives in St Louis, Missouri, USA. He is deeply interested in ancient history of India.

(আপনার

মন্তব্য জানানোর জন্যে ক্লিক করুন)

অবসর-এর লেখাগুলোর ওপর পাঠকদের মন্তব্য

অবসর নেট ব্লগ-এ প্রকাশিত হয়।